First Nations Rental Policy and Programs: Addressing Key Issues

Published March 2017 (First Nations Rental Policy and Programs - PDF version)

Acknowledgements

The development of this manual would not be possible without the FNNBOA board members and their comments. We also want to thank Naut’sa mawt Tribal Council, Vancouver Island, B.C., who has developed a similar toolkit that focuses on overall housing policies rather than on specific housing policy topics.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Rental Programs in First Nations

Examples of First Nations Communities with a Rental Program

Penticton Indian Band

Lennox Island First Nation

Atikameksheng Anishnawbeck First Nation

How Rent is Used by Chief and Council

How Rental Programs Work

Rental Incentives – Options to Consider

How to Determine Rental Prices for Housing

Option One – Percentage of Value

Option Two - Comparison

Option Three – Content of the Home

Option Four – Actual Market

Option five – Tenant Contribution

Option Six - CMHC’s Minimum Revenue Contribution (MRC) Calculation

Calculating the Total Annual MRC Required

Case Scenarios: Rent and Revenues

Scenario One

Scenario Two

Scenario Three

Community Consultation and Rental Programs

Community Engagement on Rental Regimes

Preparing the Community Rental Regime Strategy

Key Stages for Community Engagement

Step One – Community Forum/Meeting

Step Two - Presentation at Community Forum/Meeting

Step 3 – Distribute information

Step 4 - Timelines

Rent to Own or Lease Policy

Developing a Conflict Resolution System for Your Community’s Residential Rental or Tenancy Programs

Prevention

Negotiation

Mediation

Arbitration (or Adjudication)

Special Considerations for Indigenous Systems

Checklist for Designing Your Residential Tenancy Dispute Resolution System

Leadership, Values & Principles

Analyzing the Current Situation

System Design

Implementation and Continuous Monitoring and Improvement

Rental Housing Policy Template

Maintenance Check List

Appendix A

1 - Introduction

Tenancy fees, or rent, are a vital source of revenue for many Aboriginal communities, helping to pay for repairs and maintenance to Chief and Council owned homes. However, implementing a system to collect a tenancy fee, or rent, is one of the most common challenges facing many First Nations.

It is a reality that when tenancy fees or rent are not charged or these fees are not paid, many communities have little or no additional finances to make repairs to the homes they own. For many Chief and Council, tenancy fees or rent are the most important source of income that can be used to maintain homes.

The purpose of this manual is to provide Chief and Council, Housing Authorities or Housing Committees a document to support the development and implementation of a rental programs within their communities.

The manual also provides approaches to calculate rental rates and approaches to rent to own policies.

2 - Rental Programs in First Nations

Most homes in First Nations communities are owned by the Chief and Council. Homes are then provided to the members.

However, there is growing demand for more housing in First Nations communities. One way to address this need is to create rental housing. Several First Nation communities have successfully implemented a rental program.

Examples of First Nations Communities with a Rental Program

Several First Nations have successfully implemented a rental program:

Penticton Indian Band

The Penticton Indian Band in British Columbia created a new position to help tackle historical unpaid rent, and the return on investment is more than covering the new salary. The new position is shared between the Housing Office and the Social Development Office. And the new employee is filling gaps in the system that were contributing to a history of unpaid rent.

Lennox Island First Nation

Collecting rent is one of the most common challenges many First Nations face. Rent is a vital source of revenue for many Aboriginal communities, which can help support the long-term viability of their housing. But when a tenant is missing his/her rent payments, many communities have little or no recourse as to how to fix the problem. See Appendix A.

Atikameksheng Anishnawbeck First Nation

Mutual accountability helps housing office collect rent and puts community members in good financial standing.

How Rent is Used by Chief and Council

Chief and Council uses the rent paid by tenants in these main ways:

Pay for the repairs and maintenance to your home.

Pay for the staff to make the repairs and maintenance to your home.

Repay any money Chief and Council borrowed to build or improve the home.

Pay the mortgage Chief and Council is paying for the home.

Set aside some money each year to pay for larger repairs (i.e. new roof or furnace).

Allow Chief and Council to raise revenues that can be reinvested in the construction of housing or for other community projects.

How Rental Programs Work

Rent or occupancy fees are calculated monthly and should be paid in advance on or before the 28th of the month. For example, February’s rent should be paid by January 28th.

It is a condition of a tenancy agreement that a renter pay their rent in full and on time. Failure to pay on time could result in the Chief and Council taking legal action that could lead to an individual losing their home.

For Chief and Council, it is vital that rent be paid in full and on time to ensure that they have the revenues needed to conduct repairs, pay maintenance staff, pay back mortgage loans, have a contingency for large repairs in the future, and reinvest in the community.

Rental Incentives – Options to Consider

It is important that Chief and Council collect rent payments on time each month. Chief and Council may want to consider incentives such as:

A discount on the rent for tenants that can afford make rental payments on time.

A bonus or rebate - for example, $50.00 at Christmas time where rent has been paid on time.

A discount on rent that is paid electronically.

A gift card – for example, if the tenant makes 5 early payments, the first week of December, you will provide them with a bonus check or a gift card.

A penalty for late payment.

A letter of reference to tenants to help build their credit rating.

A property upgrade such as painting, new flooring, or appliances.

If rent is paid on or before the first of the month, the tenant can deduct a discounted amount. If rent is paid after the first of the month, the standard rent is due.

There could be limitations, such as incentives only applying to tenants who are not receiving any social assistance and who are in good standing by paying their rent on time for a certain period.

How to Determine Rental Prices for Housing

There is no maximum or minimum price or any fixed equation you must follow when calculating the cost of rent - the only exception is where the property is subject to an existing rent control formula based on provincial laws. In general, rental prices are determined by the local economy or demand for rental units. The price for a property is whatever renters are willing to pay for it.

However, there are general guidelines that can help you estimate a realistic price for a property.

There are several factors to keep in mind for Chief and Council. Chief and Council should consider the development of a capital replacement plan since doors (information on capital replacement planning), windows, roof and heating systems will eventually need to be replaced. Any rental charges should take the capital replacement into account.

Rent must also take the costs of insurance repairs and maintenance into account.

Here are six options for First Nations communities to consider in establishing the amount of rent to charge for a housing unit:

Option One – Percentage of Value

Calculate 1.1 percent of the home's value or the total costs of the construction costs to build the home. To do this, multiply the value of the home by 0.011.

For example, if the home is valued at $90,000, the result would by $990. For a property value of more than $100,000., the monthly rent can be expected to be lower as few people are able or willing to pay that much rent.

Option Two - Comparison

Research the rental prices of similar properties in your area. The price at which other landlords are renting properties comparable to yours will give you a good idea of where the rental market is in your neighborhood. Online rental listings and free rent-calculation tools can help you compare the rent price of properties by type and location.

Option Three – Content of the Home

Adjust the rent you charge based on the pros and cons your property offers. If the home is relatively new with up to date features, you may justify increasing your price over and above that of other properties that don't offer them.

Similarly, if your property has significant deficiencies or does not offer amenities other similar rentals include, you may have to reduce your price to stay competitive.

Option Four – Actual Market

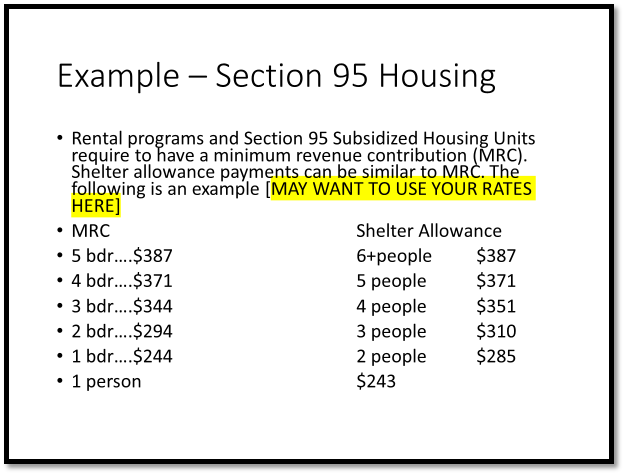

A fourth option is that rent is based on household composition. These rates are best reflected in the provincial shelter allowance rates.

Shelter Allowance is an eligible expense included under Income Assistance to recipients on reserve. The overall objectives of Income Assistance are to provide support for basic and special assistance needs of First Nations people on reserve.

Basic needs are defined as financial assistance to cover food, clothing and shelter. The shelter cost is determined by provincial legislation based on number of persons under the recipient’s application (e.g., family size, age of individuals, number of dependents other than spouse).

For example, in Ontario, a family of five can receive the maximum monthly shelter allowance of $774.00. These calculations are also used to determine the CMHC’s minimum revenue contribution for a Section 95 home.

Option five – Tenant Contribution

The income source and amount of rent to be paid is based on the gross household income of all adults age 19 or older. Under this option, consideration is given to common income sources (e.g., income assistance, seasonal employment, self-employment) and is used to determine the gross monthly income.

BC Housing (2016) has issued a Housing Provider Kit that can be used to determine the income source and amount of rent to be paid based on gross income.

Once the total gross income is determined, one can calculate the tenant rent contribution. In the examples provided, the tenant contribution is calculated at 30% (or the minimum rent, whichever is greater – this can be based on shelter allowance rates – family size) of assessable and calculable household gross income.

In other cases, the calculation has been a 20% contribution and in other situations it has been a 25% contribution. The tenant contribution may be changed at any time there is a change in household income.

Option six - CMHC’s Minimum Revenue Contribution (MRC) Calculation

This is the amount minimum required revenue contribution to the program and is used in the subsidy calculation. It must be funded annually to a specified level through collection of occupancy charges, other First Nation funds, or a combination of both.

The MRC is set at the time the project is committed. The MRC may be funded in the following ways:

Allocating First Nations funds from other sources;

Establishing a rent or occupancy charge that is collected from the tenant

A combination of (a) and (b).

MRC is an important source of funds for a Section 95 housing project. Along with the monthly subsidy payments received from CMHC, it forms the revenue base from which all project expenses are paid.

The MRC is a set amount by unit type (amount per month depending on number of bedrooms in the unit). Please refer to Schedule B of your Project Operating Agreement to verify the levels.

Calculating the Total Annual MRC Required

The total annual MRC for a project depends on the number of bedrooms per unit and the number of units in a project.

Five 1-bedroom units x MRC for 1 bedroom units x 12 months = A

Five 1-bedroom units x MRC for 2 bedroom units x 12 months = B

Five 1-bedroom units x MRC for 3 bedroom units x 12 months = C

TOTAL MRC for a 15-unit project = A + B + C

Client Selection Criteria – The criteria developed by the First Nation under a Band Council Resolution to determine eligibility and selection of occupants for housing. The selection criteria and any subsequent changes must be made known to all Band members and be approved by a Band Council Resolution and shared with CMHC.

Case Scenarios: Rent and Revenues

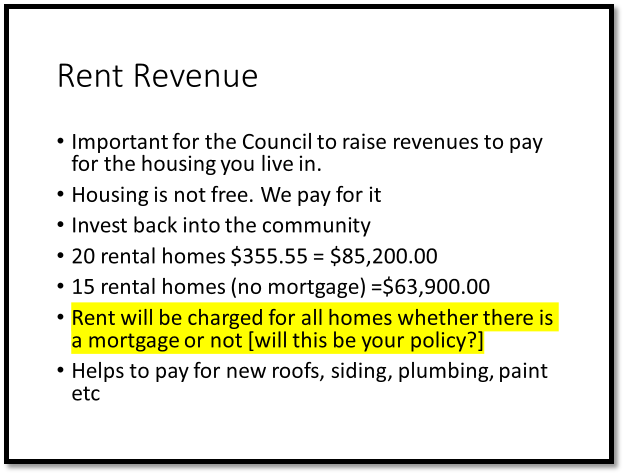

These three scenarios show how charging rent for all homes in the community can be beneficial to the community.

Assumptions:

There is no rental policy for the entire community. Consequently, AANDC will not pay for shelter allowance on homes where there are no mortgages.

Rent is not being collected for homes of individuals who are not on shelter allowance and are making income to pay rent.

The community housing stock consists of 125 homes. Among these homes, 25 have a mortgage and the Chief and Council are making the required payments (e.g., Section 95 homes). The other 100 homes have no mortgages or outstanding loans.

The families all consist of two children and two adults, and the monthly provincial shelter allowance is $360.00 per month.

The Band does not charge a percentage of operating costs to cover maintenance and repairs for each home that is allowable under CMHC operating agreement.

All homes in the community require repairs and maintenance. There is a four percent rule set aside for ongoing maintenance. For many First Nations communities, this is low percentage given the costs for repairs due to location based on the value of the house being the value of the original mortgage.

Scenario One

In this situation, rent is only charged for homes where there is a mortgage. No rent is charged for the 100 homes where there is no outstanding mortgage.

The yearly revenues from the rent are $108,000.00. However, the operating expenses include estimated costs of repairs and insurance. In this case, the First Nations is operating at a -$325,000.00 deficit each year.

| Descriptions | Totals |

| Revenues | |

| 25 homes at $360.00.00 per month | $108,000.00 |

| 100 homes (no rental revenues) | 0 |

| Total revenues | $108,000.00 |

| Operating Expenses | |

| Mortgage payments for 25 homes $360.00 per month | $108,000.00 |

| 4 percent rule set aside for ongoing maintenance for all 125 homes | $75,600.00 |

| Insurance costs per each unit $2,000.00 | $250,000.00 |

| Total Operating Expenses | |

| Less Revenue | $108,000.00 |

| Operating Deficit | -$325,600.00 |

Scenario Two

In this case, rent is being charged for all homes in the community. This generates revenues of $540,000.

However, the operating and maintenance costs will continue.

In this situation, the operating deficit is reduced by 206 percent to -$106,400.00

Scenario Three

In this situation, the Chief and Council is charging rent for all 125 units. Tenants are obliged to pay their share of maintenance costs.

The Council is also including their operating expenditures to ensure that each unit is covering costs for maintenance and repairs as part of the rental payment.

The rent charged by the Council must be at least equal to the cost of the Council’s mortgage payments. The rent must also factor in an estimate of repair costs and insurance.

In this case, the total revenues generated from the rental of homes, including operating expenditures, is $866,100.00.

The amount of revenue raised from rent covers all the operating expenditures. Most importantly, in this case, the Council has a net revenue of $432,500.00 that can be used to reinvest into building new homes or making major repairs to existing housing stock.

| Descriptions | Totals |

| Revenues | |

| 25 homes at $360.00 per month + 4 % operating Costs (50.40) + insurance ($167.00) = $577.40 | $173,220.00 |

| 100 homes at $360.00 per month + 4 % operating Costs (50.40) + insurance ($167.00) = $577.40 | $692,880.00 |

| Total revenues | $866,100.00 |

| Operating Expenses | |

| Mortgage payments for 25 homes $360.00 per month | $108,000.00 |

| 4 percent rule set aside for ongoing maintenance for all 125 homes | $75,600.00 |

| Insurance costs per each unit $2,000.00 | $250,000.00 |

| Total Operating Expenses | $433,600.00 |

| Less Revenue | $866,100.00 |

| Operating Deficit | $432,500.00 |

3 - Community Consultation and Rental Programs

Community engagement is increasingly acknowledged as a valuable process, not only for ensuring communities can participate in decisions that affect them and at a level that meets their expectations, but also to strengthen and enhance the relationship between communities and the Council. The following provides a broad overview on what to consider when planning a community consultation regarding the implementation of a rental program.

There are many books and references online that can help a housing manager develop a community consultation or engagement process. The following are some suggested references.

Social Planning and Research Council of BC – This organization has developed a community engagement toolkit that offers an adaptable approach to designing a community engagement process tailored to specific issues and/or developments in your community.

Community Engagement (BC) – This toolkit provides guidance on the issues to consider when planning and designing community engagement (PDF). It focuses on quality and effectiveness, process planning and designing engagement tailored to the particular issue, level of participation to be achieved, timeframe and range of stakeholders affected. See:

Community Engagement on Rental Regimes

Implementing change in any community can be difficult. The implementation of an occupancy fee or rent for homes in many First Nations communities is a challenge. It is important to talk about rental program as a new way forward for improving housing.

Building trust and a sense of public ownership through community consultation can create a successful foundation on which to build, if various options are presented and opinions are considered on how to implement a rental regime.

This approach will help to provide understanding on the importance of collecting rent and how it will benefit the entire community.

Lack of community consultation and failure to consider the opinions of the community may create a sense of disgruntlement and mistrust in the community.

Preparing the Community Rental Regime Strategy

It is important that a community considering rental programs be aware of the challenges and the stories of progress when implementing a successful rental program.

It may be helpful to involve people from other communities who have implemented a rental regime through in-person presentations, conference calls, radio etc. Drawing powerful lessons from those who have been through the process in other communities can help your community move forward.

It may also be helpful to hire a consultant who is familiar with change management or managing in chaos approaches. A third party can bring a different perspective and can use approaches that help build consensus on thorny issues.

Some of the key objectives and priorities in the development of a rental regime strategy includes:

Ownership of homes by the community

Pays for the repairs and maintenance to the homes

Pays for staff to make the repairs and maintenance to the homes

Repay the money the Chief and Council borrowed to build or improve the house.

Helps the Council to leverage funds to reinvest and build more homes. This will help to reduce the housing shortage

Key Stages for Community Engagement

There are four key stages that one may want to consider when doing a community engagement for rental regimes.

Step One – Community Forum/Meeting

The first engagement should be made prior to any final decisions being made by Council. This should be in the form of a well advertised community forum/meeting, where an overview on charging rent or occupancy fee are presented and questions and answer session held. The Housing Department will need to advertise the community forum/meeting to create a good communication and buy in from the community members.

If possible, a leader (e.g., an elders or cultural leaders) in the community that is respected by the community members should introduce or give the presentation. As part of this forum/meeting, consideration may be given to having an expert give the presentation who will be able to provide answers to concerns that may be raised. Motivating the community to pay a fee for housing is key for the success of any rental regime.

Key messages to the communities might include:

“rental programs give us healthy homes”

“rental programs are a part of Nation building to strengthen our community”

“Let’s collectively establish a new vision for housing in our community”

“Personal responsibilities to the home, family, community and their Nation”

Using these types of key messages will give the Housing Department a way to think about the role of the community in accepting a rental program. It will also provide the Housing Department with answers to tough questions or anticipated community responses (e.g., housing is a treaty right, they do not have the money to pay for rent).

Step Two - Presentation at Community Forum/Meeting

The following are some suggested slides (13 slides) that the Housing Department may consider using at their community Forum/Meeting (For a copy of the presentation in power point format please email FNNBOA at info@fnnboa.ca

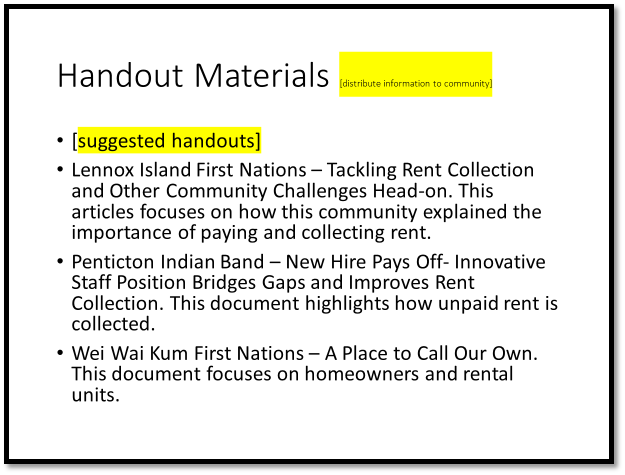

Step 3 – Distribute information

In addition to making any presentations on occupancy fees or rental programs, distributing information on how other communities are charging and collecting occupancy fees or rent can be helpful.

The following illustrates how other communities have implemented a rental policy (these documents were cited earlier in the report.

Lennox Island First Nations – Tackling Rent Collection and Other Community Challenges Head-on. This articles focuses on how this community explained the importance of paying and collecting rent.

Penticton Indian Band – New Hire Pays Off- Innovative Staff Position Bridges Gaps and Improves Rent Collection. This document highlights how unpaid rent is collected.

Wei Wai Kum First Nations – A Place to Call Our Own. This document focuses on homeowners and rental units.

Consideration may be given to telephone/conference a housing manager from a community that has established a rental regime. This will allow the community to ask this person any questions or concerns they may have on paying rent.

Step 4 - Timelines

It is important to understand the required resources (e.g., drafting the required by laws and rental agreements, hiring a consultant, developing a bookkeeping system, property management) that will need to be considered and how much time it will take to put everything in place.

If the Chief and Council have an election in the immediate future, there could be an impact on the timelines.

4 - Rent to Own or Lease Policy

In this option, Chief and Council offer rent to own or lease to own programs to assist eligible band members who are interested in homeownership and who will be able to assume full responsibility for costs associated with homeownership at the end of defined period (e.g., 20 or 35 years).

The rent to own program is available for housing units built or purchased for homeownership, through a rent to own option. The units used for rent to own or lease to own are generally built through CMHC section 95 homes.

The rent to own or lease to own policy can vary depending on how the land is entitled (e.g., the Band Council owns the homes available for rent, but the land or property is leased, and in most cases the individual owns/mortgages the home or structure). The rent to own or lease to own option depends on the management of lands in the First Nations communities.

Possible rent to own scenarios for First Nations communities:

Band Home -MRC- Shelter payment by recipient. After end of CMHC payment obligations, the home is purchased by the recipient for a specific amount.

Band Home – MRC – Individual agrees to pay the MRC. After end of CMHC payment obligations, the home is purchased by the recipients for a specific amount.

Band Home including CMHC or AANDC funding – After end of payment obligations, the home is purchased by the recipient for a specific amount.

Some rent to own or lease to own policies have specific conditions attached. For example, members who have been approved for a rent to own or lease to own must meet the terms and conditions of the rental tenancy agreement for 10 consecutive years (e.g., rental payments are made on time, unit maintenance completed in accordance with the agreement, no incidents of agreement or housing policy violations) and be responsible for basic maintenance (e.g., cleaning, repair damaged caused by tenant).

Under a lease to own, Whitecap First Nations provides up to 99-year residential leases. These leases are all legally surveyed and registered with NRCAN.

Under a rent to own or lease to own policy, the tenant(s) will be responsible for making the required minimum revenue contribution or mortgage that is being paid by the Council to CMHC. Once the debt or mortgage is paid, the home becomes the property of the tenant. The transfer to the tenant involves no funds or a minimum payment of $1.00.

In a rent to own or lease to own program, the selection criteria for a member is different than for those applying to rent a unit. Under a rent to own or lease to own program, the selection criteria can include the following:

Family circumstances (e.g., married with children)

Current living conditions

Tenancy history (e.g., payment record, evidence of responsible behaviour, length of time as a rent only tenant)

The ability to pay rent/mortgage and utilities

No outstanding debt to the community

Criminal record check

In addition, members who qualify for a rent to own or lease to own program (along with the tenant who is only renting) are required to complete a training program that includes:

A review of the First Nations Housing policy and procedures including the house maintenance schedule

Review of all the agreements to be signed by the tenant

Completion of the CMHC basic home maintenance course (to be completed within three months of moving into the unit or when the course is available)

Review of budget

Purchase rental insurance

The challenge is that First Nations may have a limited number of homes available for rent to own or lease to own programs.

These are examples of First Nations communities that have established rent to own housing policies:

Moricetown Band Council

Saulteau First Nations

Atikameksheng Anishnawbek Rent to Own Housing Program Policy provides a very good example for a rent to own agreement (appendix C)

SEMA:TH FIRST NATION, Rental Housing Policies and Procedures Manual

CMHC has developed an overview on Wei Wai Kum First Nations and how they have rent to own houses (PDF) for their members.

5 - Developing a Conflict Resolution System for Your Community’s Residential Rental or Tenancy Programs

A rental residential tenancy dispute resolution system is your entire set of dispute resolution processes mapped out on paper. It can help your community understand what the process will look like, including what choices they have in resolving their tenancy disputes, before it is implemented.

It applies equally to landlords (typically the Chief in Council) and tenants. When developing this system, it is important to remember that no one size fits all. There are many cultural differences between historical indigenous approaches to resolving disputes and western approaches, and, of course, there are many cultural and historical differences amongst First Nations. This will be addressed more fully later in this appendix.

It is important to make the dispute resolution system (“the system”) easily accessible to all users treating everyone with dignity, equality, and respect. Some of the things that need to be considered include:

Languages to be offered;

Reading level of printed materials;

Alternative arrangements for people with special needs or disabilities (e.g. telephone or video access, availability of child care, accessibility to hearing rooms, etc.);

Fair timelines;

Whether people will need assistance from a lawyer or other representative;

How power imbalances will be dealt with;

Multiple options for people to choose from when resolving their dispute;

Location and accessibility of building and meeting rooms.

It is important to seek input from the whole community (elders, men, women, landlords, tenants, people with disabilities or special needs etc.) when designing the system. This will help insure that you identify as many barriers that prevent access as possible, and that you consider the needs of the broad community so that the system is responsive to everyone.

The better the community consultation, the better the system will be in terms of acceptance, use and effectiveness.

Another way to ensure that the system will be most effective is to offer multiple options for resolving the disputes. Options can include such things as organized conversation, mediation, arbitration, and circle processes.

This allows people the opportunity to choose the process they feel most comfortable with. For example, many people do not respond well to an adversarial approach to resolving problems but instead prefer to use dialogue.

Additionally, it might be helpful to have people who are known in the community be involved in assisting the parties to resolve their disputes. Potential candidates can include:

Elders or elders’ councils

Trained local mediators and arbitrators

Trained restorative justice practitioners or facilitators

Aboriginal lawyers, judges or other dispute resolution professionals.

If the dispute goes to a hearing-style process like an arbitration, it is important that the decision-maker be impartial and independent of both tenant and landlord. This helps to ensure that the tenancy rules will be fairly and impartially applied.

Commonly disputes are resolved using either a rights-based approach or an interests-based approach.

In rights-based approaches, decisions are made based on who is right and who is wrong. They are informed by statutes, regulations, law and precedent, policy, contract, and convention. In the case of tenancy agreements, they are decided by using the rules that the community has adopted or developed to regulate the rights and obligations of landlords and tenants. Rights-based processes are adversarial and played out in front of tribunals or courts. Rights-based approaches feature decisions by a neutral third party such as a judge or arbitrator. When parties go in front of an arbitrator or judge, they give up their decision-making power to the arbitrator or judge.

In interests-based approaches, decisions are made based on what is most important to the people in the dispute. When people have a dispute, they often make demands or statements that are framed as their solutions to resolving the dispute. These statements or demands are called the person’s positions. Interests are broader than positions. Interests underlie positions and are what each party needs for satisfaction. Interests include people’s needs, concerns and hopes (e.g. shelter, safety, security, respect, and independence). Interest-based processes include focused conversations, negotiation, mediation and circles. In interest based approaches, the parties retain the decision-making power for themselves; they do not give it up to others.

There are various criteria to look at when determining which kind of process (rights-based or interest-based) is best suited for parties to a dispute. Criteria to consider include:

Transaction costs to resolving the dispute including

Time

Emotional energy

Financial cost (legal, mediator and other professional fees)

Lost opportunity

The effect that the chosen process will have on the relationship between the parties (and other affected persons)

The chances of the dispute recurring – will the result of the process be likely to endure or will the conflict continue?

The parties’ cultural familiarity with the type of process being offered.

There are many different types of processes that can be used to resolve disputes. These processes run from the very informal to very formal. The following illustration sets out some common dispute resolution processes.

The graphic shows options for resolving disputes - eithe rthe parties decide or third parties decided, informal to formal.

Prevention

In the basic dispute resolution spectrum shown above, we put emphasis on preventing disputes.

The best way to resolve a dispute is to prevent it in the first place. The adage “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” is important to remember when we think about designing a dispute resolution system. All effective systems should encompass preventive measures to help “nip conflict in the bud”. Some things that can be done to prevent residential tenancy disputes include:

· Readily available and plainly worded information about the obligations and rights of both landlords and tenants;

· Easy ways for tenants and landlords to contact each other so they can deal with problems before they escalate;

· Regularly scheduled information and feedback sessions between tenants and landlords.

Negotiation

Despite attempts to prevent disputes, they will inevitably occur. Once a dispute has developed, we recommend trying to resolve it at the lowest level and in the most cost effective way. This is through direct conversation or negotiation.

Negotiation is a face-to-face conversation between the tenant and the Housing Manager. It is organized so that they can have a safe, respectful and focused conversation directly between themselves to solve the problem as early as possible.

Sometimes it is helpful for tenants to have a friend or support person attend the meeting to help them keep the conversation on track. Simple guidelines setting out how to prepare for the meeting, and what information to gather in advance, or bring to the meeting, will make these discussions more effective.

If an agreement is reached about what is to be done to resolve the problem, the agreement is put into writing. It should clearly set out what each party must do and by when it must be done. Each party gets a copy of the agreement and its terms are enforceable in the same way that an arbitration award can be enforced.

Mediation

Mediation is a voluntary process for resolving disputes in which an acceptable, impartial and neutral third party, who has no decision-making power, assists in a face-to-face meeting between the tenant and the Housing Manager, with the aim of having them reach a mutually satisfactory agreement.

Like in the negotiation process, if an agreement is reached about what is to be done to resolve the problem, the agreement is put into writing. It should clearly set out what each party must do and by when it must be done.

Each party gets a copy of the agreement and its terms are enforceable in the same way that an arbitration award can be enforced.

Experience has shown that mediated settlements often come at less cost in both time and money, and result in more durable solutions, than disputes which have gone to arbitration.

Arbitration (or Adjudication):

If the parties chose not to go to mediation, or if they are unable to solve the issues at mediation, then they can go to arbitration. Arbitration is the final option.

Arbitration is a process in which a neutral third party renders a decision after hearing each party’s presentation.

Once the parties decide to go to arbitration, they lose control of the decision-making power and give it over to the arbitrator. Generally, there is no right of appeal from an arbitrator’s decision (which is usually called an arbitrator’s “award”).

Some systems may allow for an appeal but usually the right to appeal is quite limited, for example, if there is a question that the arbitrator may have made an error in law. There are other limited situations where the arbitrator’s award may be challenged. These include such things as:

An error of law or mixed fact and law;

The arbitrator lacked or exceeded jurisdiction;

The arbitrator was guilty of misconduct.

Special Considerations for Indigenous Systems:

When designing an indigenous residential tenancy system, cultural and historical differences between indigenous and western approaches to dispute resolution should be considered.

Western approaches are often described as more “individualistic”; whereas indigenous approaches are often described as more “collectivist” in nature.

More specifically, each community has its own unique environment and set of traditions, protocols, ceremonies, and the like that need to be taken into account when designing the system that will work best for it.

Processes that consider local traditions are more easily understood, more user-friendly, and more accepted, than those that are “taken off the shelf” and imposed on the community. The best systems are not “cookie cutter” but have been developed with significant community input.

The following table highlights some of the differences in indigenous and western approaches to the mediation process, and may provide system designers with some ideas about what characteristics would be best suited for their dispute resolution system.

Mediation Approaches: Individualist vs, Collectivist Models

| Individualistic Model | Collectivist Model | |

| Entry |

|

|

| Timing |

|

|

| The Parties |

|

|

| Individualistic Model | Collectivist Model | |

| Identifying interests |

|

|

| Negotiation and agreement |

|

|

Checklist for Designing Your Residential Tenancy Dispute Resolution System

Leadership, Values & Principles

Who will be on System Design leadership team (e.g. Housing Manager, elders, community representatives, tenant representatives etc.)

What are the principles and values for the system (e.g. accessibility, fairness, efficiency, indigenous teachings and legal traditions etc.)?

Who are the champions for change?

Who will implement the change?

Staffing the System Design Team:

Who

Decision making authority

Location in organization

Relationship with personnel and groups that are currently performing dispute resolution functions within the organization.

Clarifying Responsibilities of System Team Members & Consultant (if any):

Level of involvement and time commitment

Reporting relationship

In-team communications

Decision-making authority

Analyzing the Current Situation

An initial step in building a dispute resolution system for a community residential tenancy program is to do an analysis of the existing situation (or system, if any). The following process outline may help in that analysis.

What are the current types of disputes?

What are the major issues?

Who are the typical parties and those who get involved?

What is causing the disputes? (e.g. payment of rent, rent increases, repair to the premises, number of inhabitants in rental property etc.)

How frequent and widespread are these disputes?

How likely are these disputes to continue?

Are there factors that might contribute to increased disputes?

How are these disputes handled now?

What do people do if they have a complaint or problem?

Are there interest-based approaches available?

What do people do when interest-based approaches break down?

Are there rights-based (adjudicatory) procedures available?

What are the overall costs/benefits of these procedures? What is working well now? What is not working well?

How much avoiding takes place now? What are the costs/benefits of this approach?

How well are any of these systems working?

Are the systems being used or are they only “on the books”?

Are people generally satisfied with the processes? (e.g. perceived fairness, satisfactions with outcomes, timeliness etc.)

Are there disputes that are not addressed or are being addressed poorly, or on only an ad hoc basis?

Why are certain procedures being used or not used?

What procedures are currently available?

What is the motivation of parties? (e.g. to settle, to get attention to an issue, to protest etc.)

What are the skill levels of the parties’? (e.g. for communication, negotiation, problem solving, constructive confrontation etc.)

What resources are currently available? (e.g. people to whom disputants can go for help, dispute resolution service providers, coaches, advisors, information sources etc.)

What dynamics are working for or against change?

What are the vested interests at play for change?

What are the vested interests at play against change?

System Design

The Design Process:

Developing a collaborative and participatory process

Defining parameters and type of involvement of system stakeholders

Building in a feedback loop to receive comments, suggestions

Identification of General and Specific Goals and Outcomes for the New System

Review of diagnosis of current situation or system (if any)

Re-check for consensus

Exploring Systemic and Procedural Options

With the System Design Team, review of types of disputes and desired outcomes of the systems and procedures.

Presentation of the continuum of dispute resolution procedures and description of what each process can and cannot do.

Comparison of different procedures with types of disputes, potential/desired outcomes and potential for procedures to achieve desired change.

Selection of appropriate procedures.

Identification of different dispute resolution paths, for diverse kinds of problems or disputes, if necessary.

Sequencing the dispute resolution procedures.

Setting timelines and procedures to access and navigate the system.

Developing of appeal procedures.

Identification of personnel to manage the system.

Identification of the resources that will be needed to implement the new system.

Design Review and Commitment Process

Circulate proposed design to appropriate people/groups for input before final design in formalized.

Modify design as appropriate based on new input.

Circulate again to gain commitment and support.

Identifying Organizational Champions and Preparing Them for Work

Identify champions of the new system (formal or informal).

Prepare them to promote the new system through briefing and education.

Target groups to be persuaded or changed.

Develop a change/marketing plan.

Go Through Formal Organizational Decision-Making Channels for Final Approval

Get formal approval.

Public announcement of new program.

Develop an Educational and Marketing Plan for Affected Populations

Consider: presentations, videos, leaflets, memos, notices in newsletters etc.

Explain: How the system works, benefits to users, how to connect with the system.

Implementation and Continuous Monitoring and Improvement

Designing an Action Plan

Identification of implementation tasks.

Identification of staffing.

Assignment of tasks and responsibilities.

Development of an implementation time line and milestones.

Training System Operators

Education and marketing.

Intake.

Referral to the right process to handle the dispute.

Service providers – internal and/or external.

Quality control and monitoring.

Record keeping.

Training Parties to Use the System

Promotional and educational presentations.

Formal training programs.

Ongoing Management/Supervision

Day-to-day management and operations.

Strategic planning for the future.

Monitoring and Quality Control

Client feedback.

Observation.

Group meetings and supervision.

Systematic case monitoring and statistical record keeping.

Feedback and Organizational Learning

Making appropriate changes based on feedback from participants.

Routine and ongoing reviews of composite case data to determine how changes in the system or organizational operation can be implemented.

Ongoing Training & Education

Systems operators.

Service providers.

Clients.

6 - Rental Housing Policy Template

FNNBOA has produced a document on rental housing programs (PDF). The document provides a template for how to establish a rental program within your community.

It includes a draft by-law, a draft Band resolution and a leasing agreement.

7 - Maintenance Check List

The First Nations National Building Officers Association (FNNBOA) has developed two important documents for the Housing Departments to be given to your tenants or community members.

The Healthy Home Maintenance Checklist (PDF) gives tenants a list of items in their home that require tasks to be completed seasonally.

As a tenant renting or residing in a Band-owned home, there are regular home maintenance tasks that will help keep their home healthy.

Most tenants think maintenance is the responsibility of the Housing Department, but in many cases, it is the tenant’s responsibility. Just as regular oil changes for your car keep the engine running smoothly, keeping up with home maintenance tasks will keep your home healthy and prevent bigger problems later.

The checklist suggests items that can be handled by tenants and other tasks that should be handled by the Housing Department or contractors.

The checklist is printable and should be taped inside a kitchen or closet door.

The Basic Home Maintenance Guide for Tenants in First Nations Communities (PDF) provides an overview of the most important home maintenance repairs for tenants. The guide is a reference for tenants to conduct basic home maintenance repairs such as cleaning dryer vents; checking batteries in smoke and carbon monoxide alarms; changing filters in furnaces; and conducting a walk around to inspect the outside of the house.

Many of the basic maintenance tasks just take a few minutes.

The guide should be kept in a handy location.

If the tenant cannot do the repairs, it is best to contact the Housing Department.

We Can Customize the Checklist or Guide for Your Community

If your Housing Department wants to place their First Nations logo or information on the checklist or guide, please forward the logo in a format that can be copied and your contact information to info@fnnboa.ca

FNNBOA will place the logo/information on the document and send it back to you.

We trust you will find these documents useful.

Any comments or suggestions for improvements to these documents are welcome. Please forward them to info@fnnboa.ca